Field Notes: Mia Kivel, PhD Student, Reflects on Kris Ercums' Talk About the Art of Wang Zi

To highlight the department’s engagement with contemporary curatorial practice, we host and co-host events throughout the year that feature well-known curators and practitioners in the field. To document these events and open broader opportunities for engagement, we present “Field Notes,” where graduate contributors offer their reflections on these events. This feature comes from Mia Kivel. Mia Kivel is a PhD student in the History of Art Department specializing in modern and contemporary Ainu art. She is currently working towards her dissertation, which focuses on the relationship between Indigenous art and politics in 21st-century Ainu-moshir.

On November 13th, the Task of the Curator Collective, a graduate student organization within the Department of History of Art, hosted Kris Ercums for a virtual research talk titled “Memories of the Future: Queer Time and Space in the Art of Wang Zi.” The talk was organized as a part of a year-long interdisciplinary program titled “Queer X Contemporary X China.” Dr. Ercums holds a PhD in Chinese Art History from the University of Chicago and has spent nearly two decades working as the Curator of Global Contemporary and Asian Art at the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, where he has organized exhibitions including Staging Shimomura (2020), Debut (2021-2023), to name just a few.

Through home and studio visits and personal conversations with the artist, Ercums has developed a nuanced, sensitive interpretation of the work of Wang Zi (b. 1983), an artist who remains relatively unknown, especially outside of his native China. His multimedia practice has produced a diverse array of objects, ranging from a series of altered books intended to critique and satirize the Chinese government (one example, titled A Thousand Mile Search for the Party desanctifies a romanticized communist narrative from the Chinese Civil War by depicting partisans sitting for a sex education course) to larger installations such as If There is Still Time, which uses a multitude of different timepieces to reflect on the particular, queer sense of time that is felt by those who—like Wang Zi himself—have been diagnosed with HIV/AIDS.

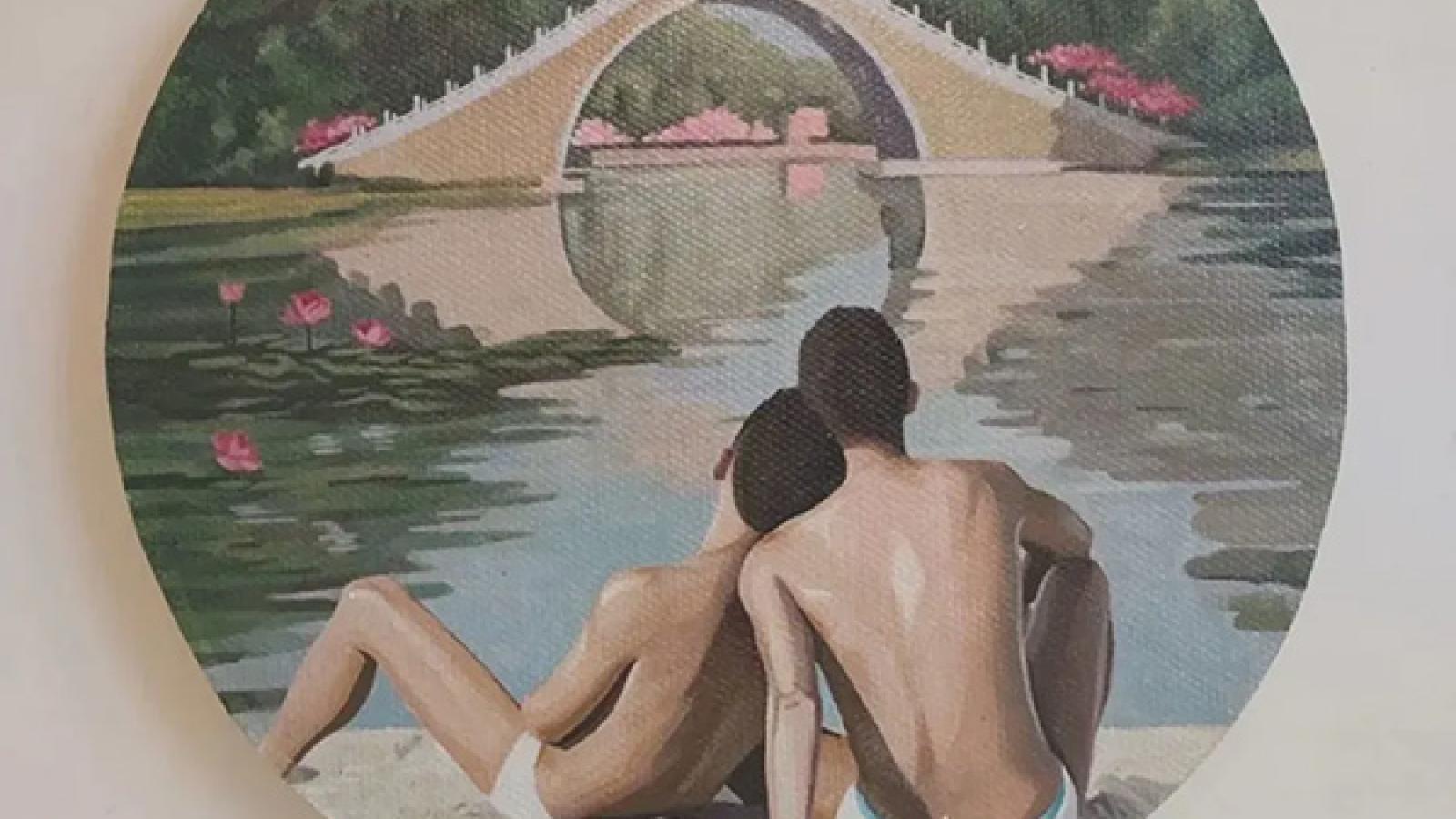

If any one artwork emerged in the talk as the most central to Wang Zi’s practice, it was I Once Thought I Could Change the World, an ongoing series in which the artist appropriates the form of late 20th-century decorative plates—often used as wedding gifts and thus potent symbols of heteronormative, domestic love—to depict imagined scenes of himself and his now deceased lover. Ercums describes these objects, which feature the couple at scenes of historical and contemporary state authority such as the Summer Palace and Three Gorges Dam, as “Memories of a future that… is now, at this point, impossible, because [Wang Zi’s] lover has passed away.” The artist has created at least one hundred individual plates for the series in a testament to the ongoing significance of their central provocation, that even amidst seemingly insurmountable authoritarianism and persecution, queer love will always find its place in the world.