John Huntington Memorialized at the Conference of the American Council for Southern Asian Art

John Huntington Memorial by Cathleen Cummings (given on April 6, 2024 at the Conference of the American Council for Southern Asian Art)

Professor John Huntington devoted his life to the study of Buddhist art, passionately exploring the communicative potential of diverse art forms. He specialized in the art, iconography, ritual, and practice of Buddhism across Asia and served as an enthusiastic advisor and mentor to many dozens of students studying Buddhist and Asian Art at The Ohio State University. His impact, on his students and on the field, is immeasurable.

John was deeply involved in ACSAA for many decades, so many of you knew him. In the brief time that I have here, I would like to tell you more about his life and work, and why those of us who were his students—now spread out all over the globe, in all sorts of teaching and museum positions—treasure our time under his tutelage.

John Cooper Huntington was born in Los Angeles in 1937 and was 84 when he passed away in November of 2021. April 6, 2024 would have been his 87th birthday. Susan Huntington, John’s wife of 51 years, is an eminent scholar of South Asian art. John is also survived by his son Eric, and daughter-in-law, Yumi. Accompanying his parents on field trips to India and other regions of Asia from his infancy, Eric is now a scholar in his own right, specializing in the visual culture, ritual, and philosophy of South Asian and Himalayan Buddhism. His commitment to interdisciplinarity in his research and teaching, reflect strongly upon John’s legacy.

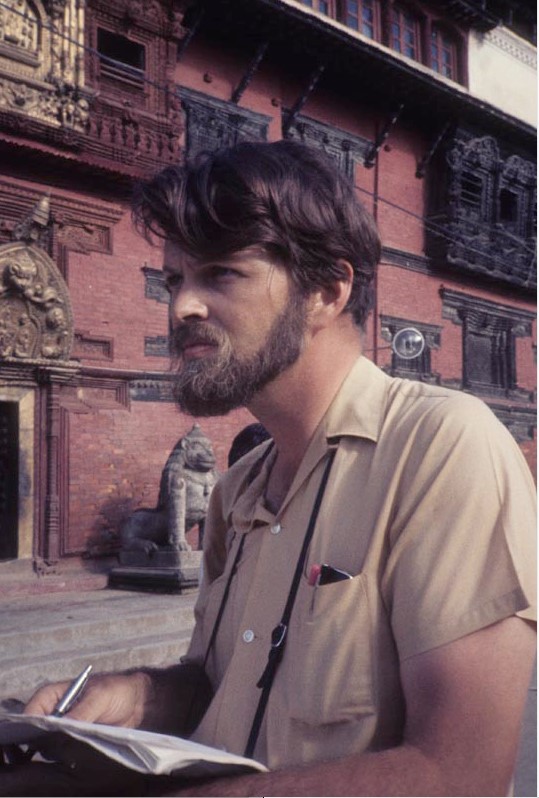

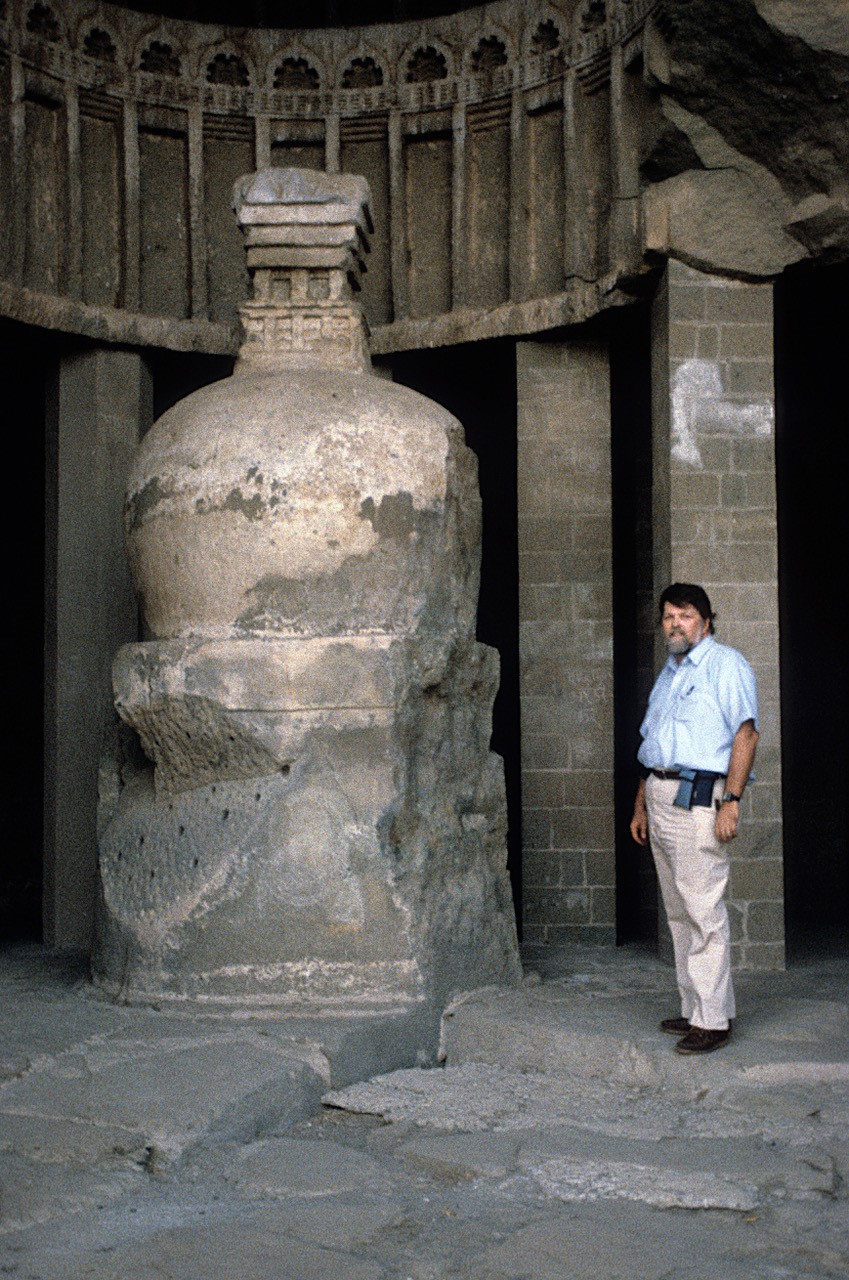

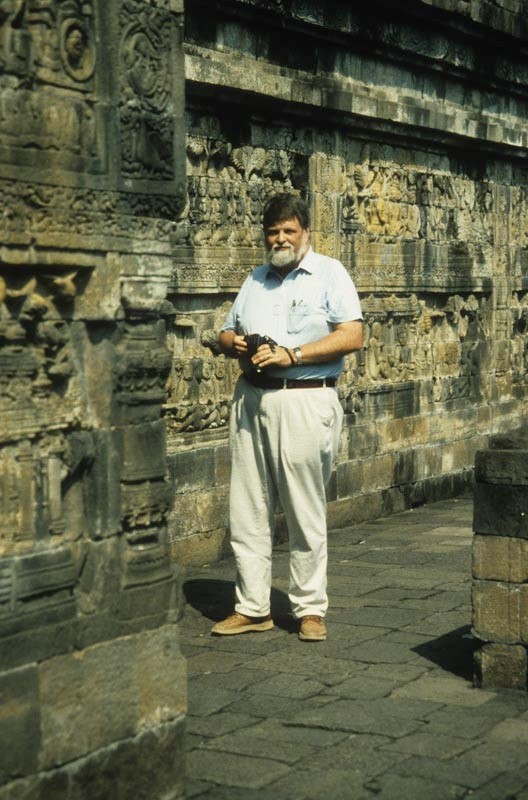

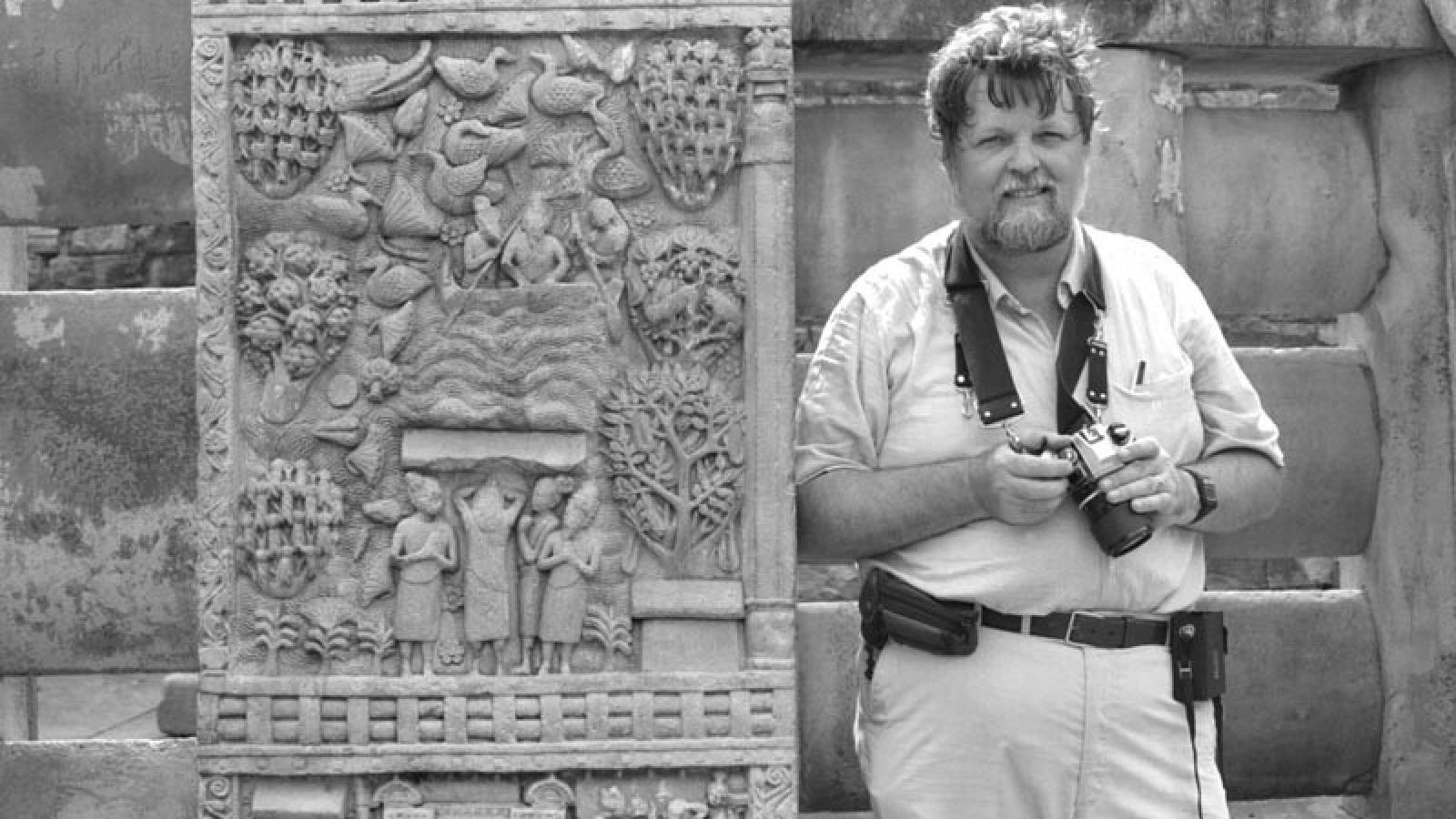

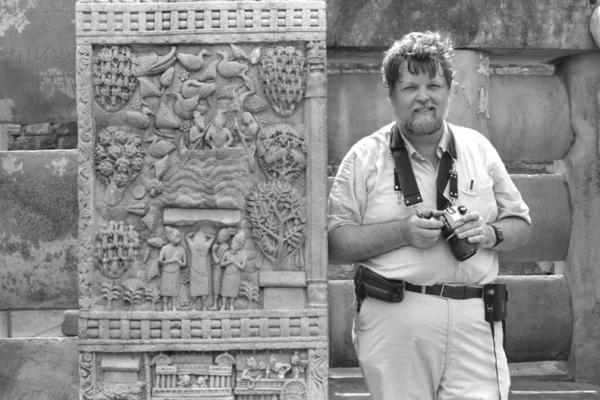

John received his PhD from the University of California, Los Angeles in 1969, writing his dissertation on “Styles and Stylistic Sources of Tibetan Painting.” Pioneering at the time, this study paved the way for what eventually became a burgeoning field of Tibetan studies. Beginning that year, 1969, John—on an NEH grant—and Susan, on a Fulbright, began the photographic documentation project that would occupy much of their lives, and that would create an ongoing and invaluable resource for scholars known as the Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art. John and Susan travelled throughout South Asia and the Himalayas documenting art in situ and in museums in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and other regions. John was trained as a professional photographer before his academic career; his photographs provide extraordinarily thorough coverage of many significant sites—some of which were part of ACSAA’s microfiche project, and later, the ACSAA slide project.

The photographic fruits of this field research, and that of many field trips over the years, became the foundation for the Huntington Photographic Archive. John and Susan strongly believed that the work they did should be shared with the educational and academic community, The public archive they created was housed at The Ohio State University for more than 30 years and is now maintained by the University of Chicago. The digital collection of the Huntington Archive includes more than 250,000 photographs of art and architecture from throughout Asia, some 80,000 of which are now accessible online. The Archive also houses a vast collection of educational resources that John created, including maps of Asia, an extensive dictionary of Buddhist terms, graphics for teaching Buddhist art, and one of the first documentary collections of art looted or stolen from Nepal and Afghanistan. All this material is accessible because John and Susan wanted to make sure that their original materials could be available publicly in perpetuity.

This was obviously a busy time in John’s life! For in the fall of 1970 he also began teaching at Ohio State, where he remained until his retirement in 2013. In those forty-three years, John helped build a flourishing program in Asian art history at OSU, and oversaw the work of some dozens of graduate students, many of whom, too, you likely know. The teamwork shared by John and Susan made the experience of studying at Ohio State especially powerful as students benefited from mentorship from both of them.

Throughout his career, John maintained a dedicated and prolific research output. Between 1969 and 2009, he authored 48 articles and essays, spanning a diverse array of topics in Buddhist art. His expertise ranged from the art and iconography of painting in Tibet, Nepal, and India, to Buddhist caves in India and China, Buddhist pilgrimage, and the iconography of key Buddhist figures. Additionally, he explored subjects like the stupas of Borobudur and Mahaswayambhu, Gandharan sculpture, the Buddhas of Bamiyan, the concept of Mt. Meru, and Himalayan painting conservation.

He authored the text The Phur-pa: Tibetan Ritual Daggers and contributed to several other key texts in the field, including The Art of Ancient India and Leaves from the Bodhi Tree: The Art of Pala India. In addition, he is responsible for two exhibition catalogues produced with the help of his graduate students: [Mirrors of the Heart Mind: The Rezk Collection of Tibetan Art from the Southern Alleghenies Museum of Art; and the monumentalThe Circle of Bliss, Buddhist Meditational Art, which he co-edited with Dina Bangdel, and with contributions by twenty of us OSU grad students.

I want to say a word more about these curatorial projects, particularly the Circle of Bliss, because I was among the students that John included in them. And to me, they exemplify John’s incredible generosity, both with his research and in his mentoring of students. The Circle of Bliss show focused on the contexts for the creation of the Himalayan Buddhist art; the catalogue runs to 560 pages and features 160 works of art. The exhibition plus its catalogue was a substantial undertaking and I am sure it would have been much easier, and much less of a headache, if John (and Dina) simply wrote the didactics and catalogue entries themselves. But John believed that we learn best by doing, and he was willing to suffer the aggravation as his grad students found their way through a dense body of material. I, for one, am especially grateful. As I delved into paintings of the Guhyasamaja-tantra. John's insight proved true: grasping these paintings required deep immersion in their practices. It was a profound learning journey.

John played an extremely important role in the history and development of ACSAA—the American Council for Southern Asian Art. From 1972-1974, John was Vice President of this organization and was thereafter a member of ACSAA’s Board of Directors. He was a principal investigator and project director, with Susan, of the ACSAA microfiche project, and was the primary photographer for several of its sets; he also contributed to the ACSAA slide project, providing slide sets on Tibetan Art, and Art of the Mauryas. Furthermore, he provided valuable contributions to the ACSAA Newsletter, offering guidance to fellow art historians. His entries covered topics such as field documentation photography (1986), slide creation for presentation (1988), and the usage of the IndicLight font that he designed for scholarly writing on South Asia, dating back to 1988.

I met John in 1996 when I began graduate study at Ohio State, after a ten-year break from being a student. I was lucky to start my first semester with an assistantship in the Huntington Archive, and through this I had a great deal of interaction with John. I recall being constantly impressed that I could show him a random slide of a sculpture at a site, and without fail he could tell me exactly what it was, what site it was from, and when he had photographed it. His breadth of knowledge and experience was staggering.

I don’t have space here to list out John’s many awards and honors, describe his contribution to other professional and academic organizations, comment on the multiple languages he had mastered, or speak more on his many other achievements. But I would like to end by citing a passage about John written by a fellow OSU grad, Sarah Richardson: “John Huntington was a towering bear, a funny smart man. He was generous and kind, possibly to fault, and was dedicated to his work, his teaching, his family … and to all of us, the extended family of his students. He made a community out of those he trained, and we are, many of us, so indebted to what and how he taught us. … He told us all that in the relatively young field of Asian art history: there will still be many big and important questions that need to be worked out, reminded us that the record was spotty and ever changing with new information, and encouraged each of us to do so fearlessly.”

John was a great mentor and a good friend and we miss him greatly.