As I listened in awe to him, talking about, almost reciting, the books he read — books in English, Turkish, Ottoman, German, Russian, Arabic and Persian — I was convinced he knew everything there was to know. And yet, just two years ago, he was kneeling at the beach with profound joy, making a sandcastle with my then 9-year-old son, not minding the ocean’s reckless waves, as if he was just beginning to discover life. The next time we met was at the same spot the following year, as he lovingly held on to his dear wife while talking about history and politics. How remarkable, I thought, for someone with such broad and deep knowledge of humankind — of their wars and genocides, spite and envy, greed and hubris — to still have faith in them. Gleeful, he shared news of his students — his extended family — and expressed his hopes for their future. I should have known, though, what was to come, despite the glow in his eyes. The sun felt colder and the wind rougher than usual at that time of the year. I should have known it was the last time I was going to see him, my mentor of two decades.

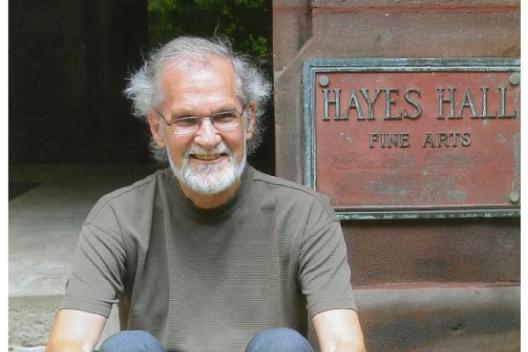

Professor Emeritus Howard Crane passed away on Thursday, March 4, 2021, at the age of 80, due to complications from COVID-19. He was a renowned historian of Islamic art and architecture, a field archaeologist and an Ottomanist with a boundless love of learning. “No, I’m not teaching,” he responded to one of my emails soon after he retired, “except trying to teach myself.” An innate curiosity about political events, past and present; a perpetual interest in built spaces, near and far; and a genuine concern for the well-being of people, known and unknown to him, determined the subjects and tone of his scholarship, teaching and conversations. While he would be mortified by my saying so, he was a benevolent mentor without pretense, a self-effacing figure who was larger than life and one of the few people I know to have lived life to its fullest.

Those of us who were lucky enough to have Professor Crane as our advisor, and even those who just took a class or two with him, know that his scholarship — and the kind he hoped his students would pursue — entailed more than just reading books (countless books!), traveling to foreign lands (really far away!), and learning languages (like software!). Scholarship, for Professor Crane, was a lifelong affair in which he engaged responsibly, thoughtfully and with much welcome humor. He cared deeply about his rapport with his colleagues and students. Yet, he would not shy from stepping in when he felt someone was erring in their argument — omitting facts or making thoughtless assumptions without care for nuance. And he knew just how — by handing them a book or a New York Times article to read, by recommending a film to watch, or, best of all, by inviting them over for a feast of Turkish food to initiate a conversation that would last into the night. As he trained new teachers and scholars, earnestly and ever so warmly, Professor Crane would keep them in check from a healthy distance, reminding them at critical moments that they are “never as good or bad as they think they are.”

Professor Crane’s education helped shape his extraordinary persona. He attended Antioch College and earned his BA from the Departments of History and English at Berea College (1964), and his MA (1971) and PhD (1975) from the Department of Fine Arts at Harvard University. He has been a prolific scholar, though I do not recall him announcing a single publication, let alone assigning to his students a text he authored.

His work has appeared in numerous edited volumes, journals and encyclopedias, including Urban Structures and Social Order: The Ottoman City and Its Parts (eds., Irene Bierman and Donald Preziosi, 1991), The Art of the Seljuqs in Iran and Anatolia (ed. Robert Hillenbrand, 1994), Encyclopedia Iranica, the Dictionary of Art, Encyclopedia of Garden and Landscape History of the Chicago Botanic Garden, The Cambridge History of Turkey, Muqarnas, International Journal of Islamic and Arabic Studies, Halı, Journal of the American Oriental Society, and the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, among others.

His Medieval Ceramics from Gözlükule, Tarsus was a product of his fieldwork in Tarsus, Turkey, which began in 2002 and helped bolster Boğaziçi University’s nascent project on medieval Anatolian archaeology. His monographs Risāle-i Mi‘māriyye: An Early Seventeenth-Century Ottoman Treatise on Architecture (1987), The Garden of the Mosques: Hafiz Hüseyin al-Ayvansarayî’s Guide to the Muslim Monuments of Ottoman Istanbul (2000), and Sinan’s Autobiographies: Five Sixteenth-Century Texts (with Esra Akın and Gülru Necipoğlu, 2006) have become reference books on Ottoman architectural history, attesting to Professor Crane’s vast knowledge of the field and prowess in the art of textual analysis.

As he spent a lifetime studying and teaching Islamic art and architecture, Professor Crane built a wide but tight network of family, friends and colleagues. Some left these memories of him:

- Howard embodied everything I once could have hoped to become when I grew up, a distinguished scholar and incredibly interesting and enjoyable guy.

- Howard was one of my favorite colleagues at Ohio State — immensely erudite but gentle, sweet, and welcoming.

- Howard was an uncommonly decent man.

- Thank you for helping show us what it means to be a great father, a true friend and a compassionate human.

- His legacy will quietly continue, as those whom he touched reach out to touch others.

- Howard’s tranquility, sophistication and gentle spirit permeated the home.

- His work deepened — via immersion and persistence — the knowledge and appreciation for Islamic culture in a wider world.

- The best teachers are immortal, since their kindness and wisdom live on in their students and continue to touch the lives of generations to come.

As I browse old emails from him, on topics from research permits and immigration to global warming and health, one line stands out. “Life takes its own course,” he writes, “and we must be grateful for what we have.” Professor Crane gave us so much to be grateful for: a love of learning, respect for relationships and compassion for the world — all greater than the sadness and grief we feel at his loss. He will be remembered affectionately and with gratitude through his scholarship, teaching, and, most of all, the love that he etched on the hearts of so many.

Esra Akın-Kıvanç, PhD 2007

Associate Professor of Islamic Art and Architecture

School of Art & Art History

College of The Arts, University of South Florida