Tell us about your current research – what kinds of questions will you be focusing on in your dissertation?

My research often explores artistic processes, lesser-studied media and the tension between fine art and craft within the fields of modern and contemporary Chinese art. Additionally, I’m interested in issues related to historiography, gender and sexuality in Chinese art and visual culture. My dissertation, “On Post-Mao Time and Space: Chinese Installation Art, 1980s-1990s,” examines the early development of Chinese installation art and its connections to transcultural artistic movements, temporality and spatiality. Now, Chinese artists (i.e. Xu Bing) are often recognized for their monumental, mixed-media installations, but the historical roots of this artistic practice have not been extensively approached by scholars in my field. My study explores how Chinese installation art challenged the rigid divisions between official art and unofficial art in the post-Mao era (after 1979).

You traveled to China for research over the summer in 2023 – tell us about some of the things you saw and explored!

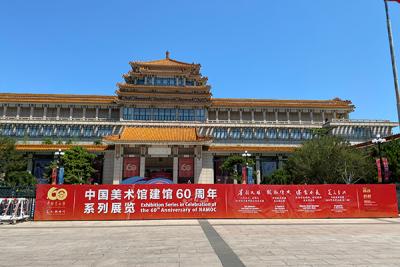

It was very lovely balanced with both family time and research trips. I didn’t see my family for almost four years, so I was very excited to see them. When I was in China, I also wanted to seize the opportunity to see as many artworks as possible. For my research, I went to Beijing and Hong Kong. In Beijing, I visited the National Museum of China, the National Art Museum of China, the Palace Museum and the 798 Art District. For the visits to the first two museums, I was companied by my friend and colleague, Yifan Li. Notably, at the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC), Yifan and I saw A Tribute to the Classics: An Exhibition of Fine Arts from the Collection of NAMOC, which featured many canonical artworks in the scholarship on twentieth-century Chinese art. It was extremely beneficial to see those artworks in person and look at pictorial details carefully.

When returning to the U.S., I made a stop in Hong Kong and visited M+ and the Hong Kong Palace Museum, both located in the West Kowloon Cultural District. At M+, I saw a special exhibition, Madame Song: Pioneering Art and Fashion in China. This exhibition was very dear to me because its curatorial focus, Madame Song or Song Huaigui (1937-2006), was closely linked to my master’s thesis, “Craft or Avant-garde? Contemporary Chinese Fiber Art at the Thirteenth Lausanne International Tapestry Biennale,” which I wrote at Ohio State in 2020. Song Huaigui was the wife of the Bulgarian fiber artist and educator Maryn Varbanov (1932-1989), who was a critical figure featured in my thesis. Varbanov established an important yet largely neglected fiber art institute at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now the China Academy of Art) in Hangzhou in 1986. On her own, Song was a fashion icon and movie star; I was blown away by her creative versatility! In this exhibition, I was surprised to see Shi Hui’s Longevity (1986), a monumental fiber artwork the artist made during her time at Varbanov’s institute. This artwork served as a case study for my thesis, and I didn’t see it in person when working on my study due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. I was beyond happy when this art-historical moment happened!

You have published several articles and book reviews over the past year – what has your experience been like working with these journals?

Working with these journals, such as East Asian Publishing and Society and ASAP/J, has been a wonderful experience. Throughout the long process of publishing either a peer-reviewed article or book review, I’ve learned the important role played by editors. For example, I received different opinions about my writing’s organization from the two anonymous peer reviewers when revising the draft of my article, “Modernizing Sculpture: Print Culture and the New Discourse on Sculpture in China, circa 1880–1929,” published in East Asian Publishing and Society (Brill). My editor intervened in this situation by kindly synthesizing comments from the two reviewers and providing a clear direction for the revision.

As someone who tends to be soft-spoken and gives in frequently, I’ve realized the importance of gently/strategically expressing why my scholarship, whether it is the choice of the topic or specific case studies, matters. This is particularly crucial when incorporating peer reviewers’ comments during the editing process. One of the two peer reviewers for my sculpture article suggested that I took a significantly different direction, which was extremely interesting, to reconsider my writing. However, when replying to my editor, I expressed why I thought it was important to not change the direction of my writing. My stance was supported by the other peer reviewer and my editor. At the production stage of my publications, I encountered a few minor non-content related mistakes either on my end or the publisher’s. My work often includes classical Chinese characters, pinyin (the romanization system for Chinese), and at times, Japanese and French lexicons, making the processes of copyediting and proofreading a bit overwhelming. However, so far, all the production editors I have worked with were kind and responsive, and they were prompted to make corrections once I noticed them. I really appreciate their input!

Keyu Yan is a PhD candidate in the History of Art Department.